Piel de agua / Skin of Water. Poemas en español e inglés

1 diciembre, 2010

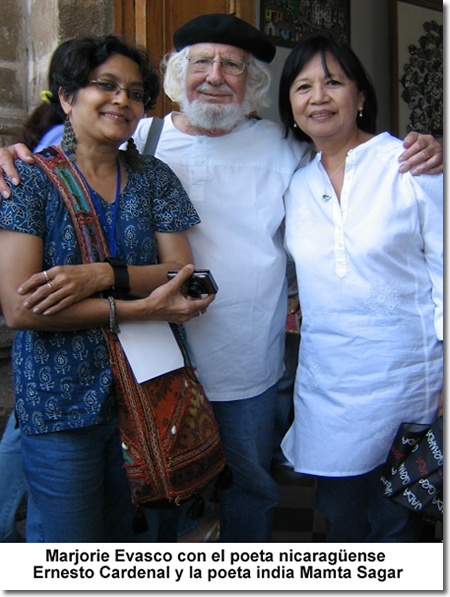

A través de las palabras, Marjorie se adentra en las vivencias del amor, la soledad y el silencio. La metáfora es el recurso que mejor privilegia a la belleza lírica para quienes deseen conocer su poesía; este año obtuvo el Premio a los Escritores del Sudeste Asiático, el más importante premio otorgado desde 1979 por la Asociación de Naciones del Sudeste Asiático (ASEAN). Carátula celebra este prestigioso galardón con la publicación de una selección poética bilingüe que lleva por título Skin of Water, traducido al español como Piel de agua.

Descarga versión PDF aquí.

KUNSTKAMMER

El campo ve, el bosque oye.

Proverbio flamenco

Yo veré, callaré y oiré.

I.

¿Y qué rastro has seguido

mientras cazabas por la noche?

Estas reliquias del Kunstkammer del bosque

recomponen la mirada celeste de tus ojos

hacia el fémur de la gacela. Aquí, una esquirla

de hueso continúa con su vuelo al aire libre.

La bala que disparaste se le clavó

en la escápula izquierda. El lazo fulgurante

de su sangre penetró el follaje negro y mojado.

Donde ella cayó, tu aliento cálido pegado a su nuca,

encontraste plumas. La tormenta tronó

entre los árboles. Y tú, inocentado

hacia el asombro, recogiste el botín de carne,

huesos y plumas resplandecientes, para el hogar.

II.

No se puede comprender este espacio salvaje

dentro de nosotros, perdidos en medio de la tormenta estival

en los ojos rojos de una loba inmensa.

Bosques sin oído, nadie cree en los proverbios antiguos.

Ni cree nadie en la verdad de los cuentos

que se contaban antaño para dormir a los niños.

El tiempo se desliza perfecto cuando un perro

choca frontalmente contra el gélido bozal de un camión.

Nosotros, callados de pie bajo un paraguas negro,

pelados de frío, viéndolo todo:

una no-secuencia, al parecer una muerte

sin trascendencia en una muerte

sin trascendencia en una autopista de entrada a Bogotá.

Tierra cruzada, tierra cruzada, campos sin ojos.

Aquí no hay cruces para los muertos.

III.

Has visto a Jerónimo después de huir

desde su infierno y su paraíso hasta su jardín

de las delicias. ¡Qué ojos y oídos de maravilla!

Nada de naturalezas muertas sino rondeles alegres, rondas

de canciones en bocas abiertas, todos los orificios

gozando, sin sombra de pereza ni calumnia.

En el panel central de El Bosco bailan figuras y

forman el gran círculo de estaciones.

Todos catan con lenguas de fuego:

flamencos, salamandras, corales rojos,

bestias, aves, hombres, mujeres, reencuentran

su ser al fluir en las aguas.

En este jardín han madurado las fresas.

Baya tras baya roja cogida y compartida.

Traducción de Marlon James Sales

KUNSTKAMMER

The field has eyes, the woods have ears,

Flemish proverb

I will see, be silent, and hear.

I.

And what spoor have you followed

when you went hunting in the night?

this Kunstkammer’s relics of the wild

reassemble your eye’s blue pursuit

of the gazelle’s femur. Here, a bone

splinter resumes her flight in air.

The shaft you let loose lodged into her

left shoulder blade. The bright ribbon

of her blood seeped into black, wet leaves.

Where she fell, your breath hot on her nape,

you found feathers. A storm had thundered

through the trees. And you, innocenced

into wonder, gathered bounty of flesh,

bones, quill by shining quill, home.

II.

There’s no figuring this wilderness

in us, lost in the summer thunderstorm

in the red eyes of a great she-wolf.

Earless woods, no one listens to old proverbs anymore.

Neither does anyone believe in the gravity of tales

once told at bedtime before dream to children.

Time slides past perfect when a dog

crashes head-on to a van’s cold muzzle.

We stand silent under a black umbrella,

knuckle-white freezing, watching it:

a no-sequence, seemingly inconsequential

road kill on a highway entering Bogotá.

Crossed earth, tierra cruzada, eyeless fields.

There are no crosses for any dead here.

III.

You’ve seen Heironymous after flying away from

their hell and their heaven into his garden

de las delicias. With what eyes and ears of wonder!

No, not still lives but rondels of joy, round

songs on open mouths, all orifices taking

to delight, without sign of slack or slander.

In Bosch’s middleway, figures dance, con-

figuring the great spiral of the seasons.

Everything tastes with tongues of flame:

flamingoes, fire salamanders, blood corals,

beasts, birds, men, women, restore themselves

unto themselves as they go round the waters.

In this garden, strawberries have ripened.

Berry by one red berry picked, partaken.

LA CONDICIÓN HUMANA

Así es como vemos el mundo

Rene Magritte, 1938

Hay un cuarto donde un hombre está tendido

Junto a una mujer cuyos hombros están iluminados

Por la mañana. Él la despierta a la deriva

De nubes, turbulencia de cielos, llovizna

De hojas en el aire. “Magritte”,

Le dice él a ella al oído, trazando

Con un largo dedo delgado

Un marco más allá del marco de la ventana.

Otro cuarto en otro tiempo

De pronto se abre dentro de ella.

Ella está de pie junto a la ventana

Frente al espacio de hierba de la pintura,

El corte de un sendero, y en el horizonte

Un muro de montañas midiendo el alcance

De un único álamo. La Condition Humaine,

Se vuelve ella hacia el hombre a su lado,

Como diciendo que comprendía la forma como adentro

Y afuera de los cuartos del amor

El paisaje no siempre fue de una pieza;

Cada vez que ella tornaba su corazón en palabras

Para inventar la verdadera forma de ser,

Motas de polvo ya estaban atrapadas

En la luz de las imágenes, como esta mañana

Que desapareció rápido y se volvió otro día.

En seguida, cada cual estará en otra parte.

Traducción de Nicolás Suescún

LA CONDITION HUMAINE

This is how we see the world.

René Magritte, 1938 lecture

There is a room where a man lies next

To a woman whose shoulders are lit

By morning. He wakes her to drift

Of clouds, wash of skies, drizzle

Of leaves in the air. “Magritte,”

He says into her ear, tracing

With a long slender finger,

A frame beyond the windowpane.

Another room in another time

Suddenly opens inside her.

She is standing by a window

Before the painting’s expanse of grass,

The cut of dirt road, and on the horizon

A stand of mountains measuring the reach

Of a single aspen. “La Condition Humaine,”

She turns to the man beside her,

As if to say she understood how inside

And outside the rooms of love

The landscape was not always seamless;

How, every time she turned her heart

Into words to invent the true form

Of being, dustmotes were already trapped

In the light of images, like this morning

Vanished fast into another day.

In no time they shall each be elsewhere.

MIEL

¿Qué vas a hacer con los veinte kilos de miel

De las seis colmenas que cuidaste largo tiempo?

No te propones feriar el trabajo paciente de las abejas

En sus perfectas ciudadelas de dulzura, sirviendo

A una sola reina a la vez: la más fuerte, la más fecunda

De las majestuosas hembras, segura de la pureza

Del polen y del néctar, que prueba en grados de color y fragancia

En los jardines que la rodean, y alimenta del todo su ciudad.

En la primavera pasada uno de tus enjambres se fue

Al peral de tu vecino y tuviste que probar tu ingenio

Para atraerlas de nuevo a tu huerto, donde los ciruelos

Acababan de empezar a recobrar el ánimo de retoñar

De nuevo después de siete años de estar dormidos.

Este verano, recogiste ciruelas maduras y jugosas.

¿Qué podías hacer con cinco canastas de ciruelas?

Tantas no se pueden comer ni congelarlas mucho tiempo.

En mi lado del mundo esta noche, después de las lluvias,

Unas abejas sueltas llevando sus trajes negros con franjas

Amarillas zumbaban en torno a la lámpara de mi estudio

Para secar sus alas. Han estado haciendo esto durante

Todo la estación de los monzones, abandonando

La colmena en el tamarindo en el jardín de mi vecino.

Un amigo, también apicultor, dice que se comportan así

Porque están ciegas y viejas y buscan el calor para morir.

¿Y ahora qué hago yo con una caja llena de abejas muertas?

Traducción de Nicolás Suescún

MIEL

What would you do with twenty kilograms of honey

From the six hives you’ve kept through the seasons?

You have no intent of bartering the bees’ patient work

In their perfect citadels of sweetness, serving only one

Queen at a time: the strongest, most fecund of stately

Females, sure of the purity in pollen & nectar, sipped

In gradations of color and fragrance from gardens

Surrounding her and feeding her city to fullness.

In last year’s spring you had a swarm that went

Up your neighbor’s pear tree and you had to prove

Your mettle at luring them back into your garden,

The plums just beginning to pluck their courage

To blossom again after seven long years of sleep.

This summer, you’ve picked juicy ripe plums.

What could you do with five baskets of them?

You can only eat so much or freeze them so long!

On my side of the world tonight, after the rains,

Stray honeybees wearing their striped yellow

And black suits buzzed around my study lamp

To dry their wings. They have been doing this

This entire monsoon season, leaving the hive

From the tamarind tree in my neighbor’s garden.

A friend, also a beekeeper, says this behavior tells

They’ve gone blind, old, & come to the warmth to die.

Now, what do I do with a boxful of dead bees?

SIC TRANSIT MUNDUS

Este debe ser el gusto del lenguaje—

la lengua delineada por muchos colores,

analizada por las sílabas de la memoria,

el paladar la bóveda de un mundo

circunscrito por consonantes, cuyos

bordes sugieren lo agridulce de las naranjas,

la cáscara verde del melón amargo, el olor

de río de los mangos hasta en el huerto.

Cuando canto sobre Balicasag, isla

cuyo nombre inscribe el cangrejo con las patas

hacia arriba, estoy traduciendo la historia

de las llamas que arrasaron toda una aldea

cuando se luchaba por la revolución.

En el mes en que nacen los delfines,

las madres tejiendo esteras de pándano

se detienen para contar la historia

de cómo sucedió en un día de mayo,

en el mes de las fiestas en Bohol:

Al alba las campanas repicaron locas.

Alguien había prendido fuego al huerto

del padre Domingo del Valle;

para el mediodía hasta los grillos

se habían vuelto cenizas.

Yo canto esta historia para que pruebes

el aroma del arroz milagroso hirviendo

en la estufa de tierra, o que toques

desde tu ventana abierta

un banco de delfines jugando cerca

de la costa. Y yo quiero que el dejo

de ácido en el aire refresque los bordes

de tu boca, como si hubieran árboles

invisibles a barlovento, todavía

madurando bajo el sol ardiente.

para Franz Arcellana nacido el 6 de sept., 1916

Traducción de Nicolás Suescún

SIC TRANSIT MUNDUS

This must be the taste of language–

the tongue mapped by many colors,

parsed by the vowels of memory, the roof

of the mouth the dome of a world

circumscribed by consonants, whose edges

suggest the sour-sweetness of oranges,

the bittermelon’s green rind, the river-

scent of mangoes all the way to the grove.

When I sing of Balicasag, island

whose name inscribes the upturned

crab, I am translating a story of fire

razing a whole village to the ground

when the revolution was fought.

In the month dolphins are born,

mothers weaving pandan mats

pause to tell the story

of how it happened one day in May,

in the month of fiestas in Bohol:

The churchbells rang mad at dawn.

Someone had set fire to the orchard

of Padre Domingo del Valle;

by noon even the grasshoppers

had turned to ashes.

I sing this story now to let you taste

the aroma of milagrosa rice boiling

on the earthen stove, or catch

from your open window

the pod of lumba-lumba playing near

the island’s shore. And I want

the edges of your tongue to water

from the hint of acid in the air, as if

invisible trees stood windward, still

ripening in the burning sun.

for Franz Arcellana born Sept. 6, 1916

VIDA PARISINA

(A la manera de Juan Luna, 1892)

¿Qué imagen tendrían de ella

En su pintura, sola al atardecer

Esperando en un café de París?

Tal vez uno de ellos se acercará lo bastante

Para captar un dejo de ajenjo en su aliento,

Y ella le susurraría: hay una calle que va

Hacia el sur hasta una vieja estación de tren

Donde muchas historias han dejado su sinsabor

En los bancos de hierro forjado. Y podría decir

Que hay un río en cuyas riberas uno podría

Caminar diez millas hasta una aldea donde el mimo

Y el tonto bailan una historia de amor como un duelo:

Había una vez una mujer y un hombre

Enmudecidos por las rosas, acosados por los rayos.

Y las abejas hicieron que se postraran de rodillas.

Ella es la mujer sentada allí, sola en un café

En París al atardecer, sin esperanza ni lamentos

Pero a tiempo. Como si cada momento ahora

Pudiera ser el principio de una historia diferente.

Traducción de Nicolás Suescún

PARISIAN LIFE

(After Juan Luna, 1892)

What would they make of her

In his painting, alone at dusk,

Waiting in a café in Paris?

Perhaps one of them will peer close enough

To catch the hint of absinthe in her breath,

And she could whisper to him: there is a street

Going south to an abandoned train station

Where many stories have left their remorse

On the wrought-iron benches. She could say

There is a river on whose banks you could

Walk ten miles to a village where the mime

And the fool danced a love story like a duel:

There once was a woman and a man

Struck dumb by roses, pursued by lightning.

They were brought to their knees by bees.

She is the woman who sits here, alone in a café

At dusk in Paris, not in hope nor in regret

But in time. As if every moment now

Could be the beginning of a different story.

CUERPOS DE ORO

(a la manera de Woodland Path in Iowa City, C.W. Kent)

El araguaney se vuelve cobre y oro ahora.

Mi hermano pintó su resplandor

El año que se perdió en Venezuela.

Fue este árbol ardiente de la memoria

Lo que lo llevó de nuevo al primer hurto

Cuando el ojo humano vio el fuego del dios,

Chamuscando la imaginación para que despertara

Encontró el camino fuera del bosque cuando

Semilla, flor y tronco fueron forjados en las llamas.

Así es nuestro paseo mañanero en este día luminoso—

La búsqueda del cuerpo despierto en los árboles

De pie rojos, bronce y ocre, en Iowa.

Vivimos para abrirnos camino con palabras,

Para realzar el color de todos los ocasos de un año

Guardando el color en la savia fluyendo, en cada retoño

Ardiendo de vuelta siempre en la noche inevitable

Prevemos el tiempo cuando la tierra se va a recoger,

Pero ahora en el Parque Squire Point, de pronto entramos

En una senda encendida del bosque, los arces de miel

Caldeados: esta sombrilla amarilla de aire nos envuelve,

Expósitos del dios que sopla fuego.

Para Hansel Mapayo y Katie Ives

Traducción de Nicolás Suescún

BODIES OF GOLD

(After C.W. Kent’s Woodland Path in Iowa City)

Turns copper-gold the araguaney now.

My brother painted its shimmer

The year he lost himself in Venezuela.

It was this burning tree of memory

Led him back to that first theft

When human eye beheld god’s fire,

Singeing the imagination to waking.

He found his way out of the forest when

Seed, flower and trunk were forged in flame.

Such is our morning hike this sunlit day—

A quest of waking the body up to the trees

Standing red, bronze and ochre in Iowa.

We live to forge our way with words,

Bring out the colors of an entire year’s sunsets

Kept warm in the running sap, each fingertip-leaf

Burning back always into inevitable night.

We foresee the time earth will fold unto itself,

Yet now in Squire Point Park, we suddenly step

Into a woodland trail ablaze, the sugar maples

Simmering: this yellow umbrella of air engulfs us,

Foundlings of the god who breathes fire.

for Hansel Mapayo and Katie Ives

DOS FRAGMENTOS DEL DIARIO ÍNTIMO

(para Frida Kahlo)

I. El Galeón de la Alegría

Fuera del astillero del cuerpo, tu galeón de luz navega hacia la Otra Orilla, sus coordinadas fijas en los ejes de la soledad y el deseo.

En esta singular empresa, uno es el jugador que apuesta todo —la rica provisión en el baluarte de tu alma— para restaurar, para rehacer lo deshecho: una pierna atrofiada, un miembro amputado, un pie triturado, una columna vertebral astillada treinta veces, un vientre que no podía contener lo que habría sido tu hijo o tu hija.

Para el único marinero a bordo, tu mellizo, tu doble, tu amada que está en todas las mujeres que amas, anuncias las ocho direcciones cardinales a favor del viento, tu voz entrecruzando los naranjales que maduran cerca del puerto: Estrella Polar, estrella del Norte, playa del Sur, viento del Oeste, sol de Oriente, Sobre la tierra, Bajo el cielo, Tras el horizonte, Frente al destino —¡Defenderse de los cabrones!

Soltando las velas de lona blanca, ella grita de vuelta: ¡Ay, ay amada! ¡Nunca pintes tus sueños! ¡Pinta tu realidad!

Cuando tenías seis años, respiraste hasta que se empañó el vidrio de la ventana de tu alcoba que daba a la calle Allende, y en su superficie transparente dibujaste una puerta secreta. Por esa puerta con sigilo fuiste a Pinzón, la tienda vecina donde vendían leche fresca, queso madurado y miel silvestre. Y a través de la letra O descendiste al corazón oculto del laberinto donde una muchacha de tu edad, tu amiga más intensa, siempre te esperaba para escucharte y bailar hasta aliviar el dolor en tu canción.

Ella fue la que primero supo tu otro nombre cruel, el que decían los niños insensatos a tus espaldas: ¡Pata de palo! ¡Cojitranca! Y te dio el don de su nombre, Alegría, su risa y su malvado ingenio curando todas mis heridas. Con los años creció contigo, dentro de ti, y fue toda su voz unida a la tuya en tus carcajadas, tus leperadas. Abrió la puerta que la separaba de ti cada vez que te reías profundo y jurabas como un marino borracho.

Fue por ella que dibujaste el mapa de los cielos nocturnos, antes de que te amputaran hasta la rodilla la pierna con gangrena, como si la noche tuviera mil ojos de sonámbulo, todos muy despiertos, llorando como La Llorona. Levantándose de tu mar de lágrimas negras de tu cuerpo, danzó tu milagro de levedad, tus alas verdes naciendo en tus clavículas cuando le gritaste: ¡Pies pa qué los quiero /Si tengo alas pa volar!

Y allí, en el altar de Coatlicue, ofreció ella una réplica de plata de tus pies, el izquierdo reseco, el derecho, roto. Y la Diosa la recibió con sus propias manos laceradas, su falda de rojas serpientes silbando.

II. Amor y muerte

Tus ojos se abren, siempre viendo, y pintas tres imágenes de tu muerte en las últimas páginas de tu diario íntimo.

La primera, un paisaje ferozmente dibujado con gruesas líneas negras, desnudo y estático, está tan vacío como la casa pintada con unos espantosos tonos rosados y verdes. Y arriba, el severo azul del cielo. Y abajo, un caballo amarillo pálido galopando, galopando.

Tras sus resonantes cascos en la calle de esta aldea abandonada en la última frontera del tiempo, ella oye a lo lejos la canción que le cantaste al hombre que deseabas, que siempre estaba ausente: Tú estás aquí, intangible, y tú eres todo el universo al que doy forma en el espacio de mi habitación… Tu presencia flota por unos instantes como envolviendo todo mi ser en una ansiosa espera de la mañana. Caigo en la cuenta de que estoy contigo. En ese instante todavía pleno de sensaciones, mis manos hundidas en naranjas, mi cuerpo se siente rodeado por tus brazos.

¿Cómo deja el Amante a la Amada? Ciertamente no como el caballo sin jinete, corriendo sin rumbo locamente?

Tus ojos arden en los suyos en respuesta: La angustia y el dolor, el placer y la muerte no son más que un proceso… Yo nunca pinto sueños. Yo pinto mi propia realidad.

Ella vela contigo mientras trabajas en tu último díptico: Caos de lluvia cayendo del vientre del cielo escindido. Se apoya en su silencio y escucha tus días insomnes como tu último, más íntimo retrato adquiere su forma: en tu cabeza un halo rojo de sangre reseca, en tus espaldas unas alas verdemente abiertas, levantando todo tu cuerpo, transfigurado, cubierto por un cielo carmesí.

En esta última mañana, al dormirse profundamente, ella abre una página en blanco de su diario íntimo y escribe los versos de una canción de cuna para ti:

La madrugada

¡Ay, ay Frida!

Tus manos hundidas

en las naranjas.

¡Abrázame en tu pena,

libérame en tu risa!

Traducción de Nicolás Suescún

TWO FRAGMENTS FROM DIARIO INTIMO

(for Frida Kahlo)

I. El Galeón de la Alegria

Out of your body’s shipyard, your galleon of light sails for the Other Shore, the coordinates set on the axes of solitude and desire.

In this singular enterprise, you are the gambler who wagers all—the rich provisions in the hold of your soul—to restore, to make whole everything broken: a withered leg, a cut limb, a crushed foot, a spine splintered thirty times over, a womb that couldn’t hold what would have been your son or daughter.

To the only hand on deck, your twin, your double, your beloved who is in all the women you love, you call out the eight cardinal directions downwind, your voice crisscrossing the ripening orange groves near the harbor: Northern star, Southern shore, Western wind, Eastern sun, Above the earth, Beneath the sky, Behind the horizon, In Front of destiny– Defenderse de los cabrones!

Unfurling the white canvas sails, she calls back: Ay, ay Amada! Nunca pintes tus sueños! Pinta tu realidad!

When you were six, you breathed onto the glass pane of your room’s windows facing Allende street till it misted over, and on its transparent surface you drew a secret door. Through the door you stole away to Pinzón, the neighboring store that sold fresh milk, aged cheese and wild honey. And through the letter Ó you descended to the hidden heart of the labyrinth where a girl your age, your intensest friend, always waited to listen to you and dance to lightness the ache in your song.

It was she who first knew of your cruel other name, the one the mindless children called you by behind your back: Pata de palo, Pegleg! And she gave you the gift of her name, Alegría, her laughter and wicked wit healing all wounds. Through the years she grew with you, inside you, and it was she whose voice joined yours in your caracajadas, your leperadas. She swung the door open between you every time you laughed from your belly and swore like a drunken sailor.

It was for her you drew the map of the night skies, before they cut your gangrenous right foot off at the knee, as if the evening had a thousand somnambulists’ eyes, all of them wide awake, weeping like La Llorona. Rising from your body’s sea of black tears, she danced your miracle of weightlessness, your green wings sprouting on your shoulder blades when you cried out to her: Pies pa qué los quiero / Si tengo alas pa volar!

And there, on the altar of Coatlicue, she offered a silver replica of your feet, the left, shriveled, the right one, broken. And the Goddess received them in her own lacerated hands, her skirt of red serpents hissing.

II. Amor y Muerte

Your eyes open, always seeing, you paint three images of your death on the last pages of your diario intimo.

The first, a fiercely drawn landscape in black bold lines, stark and still, is empty as the house painted a ghastly pink and green. Above, the unmitigated blue of sky. Under it, a pale yellow horse galloping, galloping.

In the wake of its echoing hooves on this deserted village street at the last frontier of time, she hears from afar the cadenza of the song you sang to the man you desired, who was always absent: You are here, intangible and you are all the universe which I shape into the space of my room…Your presence floats for a moment or two as if wrapping my whole being in an anxious wait for the morning. I notice that I’m with you. At that instant still full of sensations, my hands are sunk in oranges, and my body feels surrounded by your arms.

How does a Lover leave the Beloved? Surely not like the horse without the rider, running mad to nowhere.

Your eyes burn into hers as you answer: Anguish and pain, pleasure and death are no more than a process…I never paint dreams. I paint my own reality.

She keeps vigil with you as you work on the last diptych: chaos of rain falling from the belly of heaven cut wide open. She leans on her silence and listens to you sleepless for days as your last, most intimate self-portrait takes shape: on your head a red halo of dried blood, on your back your wings outspread greenly, lifting you whole, your body, transfigured, embraced by a crimson sky.

On this last morning, as you fall into deep sleep, she opens a blank page of her diario intimo and begins to write the first lines of a lullaby for you:

La Madrugada

Ay, ay Frida!

Tus manos hundidas

en las naranjas.

Abrázame en tu pena;

libérame en tu risa!

Translations in English of excerpts of Frida Kahlo’s diary are by

Barbara Crow Toledo and Ricardo Pohlenz in the commentaries

on the diary by Sarah M. Lowe, in The Diary of Frida Kahlo.

Mexico City: Banco de Mexico, trustee for the Diego Rivera

and Frida Kahlo Museums, Mexico, D.F., 1995.

DESPEDIDA

(El homenaje a Ted Berrigan y Federico García Lorca)

Si muero, dejad el balcón abierto

Federico García Lorca, Despedida

Juan Rulfo está muerto. Hace veintiún años, se trasladó

con muslos pálidos a los árboles de sueños de Comala.

Hoy despierta a la luz de mi habitación.

Levantándose para preguntar a mis ojos,

en tonos tiernos:

¿A dónde vas, Margarita?

Quiero decirle:

Voy a la casa de Pedro Páramo, a tu pueblo

de los muertos que aman, desean, matan por pasión o esperan

como si la puerta de la vida nunca se hubiera cerrado de golpe.

En vez de eso le cuento que otra Margarita,

de apenas dieciocho años,

que, corneada en el vientre por un toro,

al dar a luz una niña al mediodia, casi se desangró.

Condenada a morir a las cinco de la tarde, su vida cruzó

el umbral y dejó el balcón abierto al sol.

Traducción de Alice M. Sun-Cua y Jose Ma. Fons Guardiola

DESPEDIDA

(after Ted Berrigan and Federico Garcia Lorca)

Si muero, dejad el balcon abierto

Federico García Lorca, Despedida

Juan Rulfo is dead. Twenty one years ago, he moved

With pale thighs to the dream trees of Comala.

Today, he awakens to the light of my room,

Rising to meet my eyes, asking in tender tones:

A donde vas Margarita?

I want to say to him:

Voy a la casa de Pedro Paramo, in your village

Of the dead who love, lust, kill in passion, or hope

As if the door of life had never slammed shut.

Instead, I tell him of another Margarita, barely 18,

Giving birth to a daughter at high noon, gored

In the belly by the bull’s horn, almost bled dry.

Doomed to die at five in the afternoon, her life crossed

The threshold and opened the balcony to the sun.

LOS PENDIENTES PERDIDOS DE LA LUNA

La primera Luna casi llena de junio

se asoma sobre el jardín-laberinto.

Le oigo subir la falda

por encima de los muslos, mientras los dedos esbeltos

de la noche arrancan la primera nota de dolor

en su corazón. Extiende los brazos

a la luna bruñida y se la coloca

en su lóbulo izquierdo como un pendiente perdido.

En este mes de flores que rebosa

con dos lunas llenas, canta por el hallazgo

del otro pendiente perdido. Extenderá

los brazos, lo colocará en su lóbulo derecho.

Luego, bailará su danza del fuego

debajo de la luna azul. Sola, o acompañada.

Traducción de Alice Sun-Cua y José Ma. Fons Guardiola

LUNA’S LOST EARRINGS

The almost-full first moon of June

Rises above the labyrinth garden.

And I hear her gather her skirt high,

Up her thighs, as the slender fingers

Of night pluck the first note of ache

In her heart. She stretches out her arms

To the burnished moon and puts it on

Her left earlobe like a lost earring.

In this month of blossoms brimming

With two full moons, she sings of finding

Her other lost earring. She will stretch out

Her arms, put it on her right earlobe.

Then, she will dance her dance of fire

Under the blue moon. Alone or With.

ORIGAMI

Esta palabra se despliega, busca viento

para acelerar el vuelo de la grulla

al norte de mi sol, hacia ti.

Le doy forma a este poema

de papel, plegando

las distancias entre nuestras estaciones.

Este poema es una grulla.

Cuando despliegue sus alas,

el papel quedará puro y vacío.

Traducción de Alice M. Sun-Cua y Jose Ma. Fons Guardiola

ORIGAMI

This word unfolds, gathers up wind

To speed the crane’s flight

North of my sun to you.

I am shaping this poem

Out of paper, folding

Distances between our seasons.

This poem is a crane.

When its wings unfold,

The paper will be pure and empty.

Maribojoc, Isla de Bohol, Visayas, región central del archipiélago de Filipinas, 1953.

Es doctora en letras por la Universidad de Filipinas. Escribe en dos lenguas, el cebuano y el inglés. Enseña escritura creativa en la Universidad de Manila. Entre sus libros destacan Tejedoras de sueños (Poemas escogidos, 1976-1986), Tonos ocres (1999) y Piel de agua (Poemas escogidos, 2009).